by Elizabeth Cerejido, Ph.D.

Ramón Grandal (b. Havana, Cuba, 1950; d. Miami, FL 2017) is one of Cuba’s pioneering photographers who emerged onto Havana’s photojournalistic scene in the 1970s. Along with other prominent figures from that generation including José Figueroa, Enrique de la Uz, Ivan Cañas, and others, Grandal approached his subjects and scenes from daily life with a keen eye for both the documentary (the “real”) as well as the artistic. In addition to his street photography, his best-known bodies of work include portraits of artists and intellectuals; Cuban theater; and a series on colonial Cuban architecture that was reproduced in the second edition of Alejo Carpentier’s famous book La ciudad de las columnas.

Grandal exhibited widely and his work can be found in major museums around the world including Musée de L’Elysée, Switzerland; Photoforum Pasquart, Switzerland; the Mexican Council of Photography; Casa de las Américas; the National Museum of Fine Arts of Havana; and the Museum of Fine Arts in Caracas, Venezuela, among others. He emigrated from Cuba to Venezuela in 1993, where he lived with his family for over twenty years. There he continued to exhibit and work as a professional photographer until settling with his family in Miami, where Grandal died in 2017. The Cuban Heritage Collection is proud to be the repository of Ramón Grandal’s photographic oeuvre.

Below is an interview with Kelly Martínez Grandal, poet, author, editor, and daughter of photographer Ramón Grandal, with whom we worked closely on this important acquisition. I also want to acknowledge that portions of Grandal’s archive were donated thanks to the generosity of Kelly and her mother, the photographer Gilda Pérez.

EC: I first learned of Grandal’s work while doing research for my master’s thesis which focused on the role of photography in Cuba during the 1970s. I was interested in how it circulated and how it functioned beyond its propagandistic or documentary dimensions especially against the backdrop of “el quinquenio gris” (as the first part of that decade was known due to its repressive and retrograde cultural policies). Yet, I found that there were spaces for artistic and editorial experimentation such as in Cuba Internacional and Revolución y Cultura, led by artistic directors Luc Chessex and Aldo Menéndez, respectively, where Grandal’s work featured prominently.

The kind of realism that defined Grandal’s photography stood in large contrast to the utopian and triumphant visual narratives of the previous generation from the 1960s. What can you share about Grandal’s role within this particular historical moment? What did it mean to be a photographer at a time when photography was not considered an art form?

KMG: I do not believe that this decision to break up with the previous generation was a calculated one. He was a rebel by nature and probably that is why he found in photography a way of self-expression. We are used to photography, and we forget the transgression that its invention meant to the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. That decision answered his own private necessity for saying things as he wanted to; a loyalty to himself and his own points of view that always defined who he was and what he did, for better or worse. At the beginning of the 70’s, Luc Chessex showed him The Americans, the iconic book by Robert Frank, and my dad thought: this is what I want to do with Cuba and Cubans. He was deeply interested in people and street life as they really were, even when we know (and he knew) the artificial component in photography.

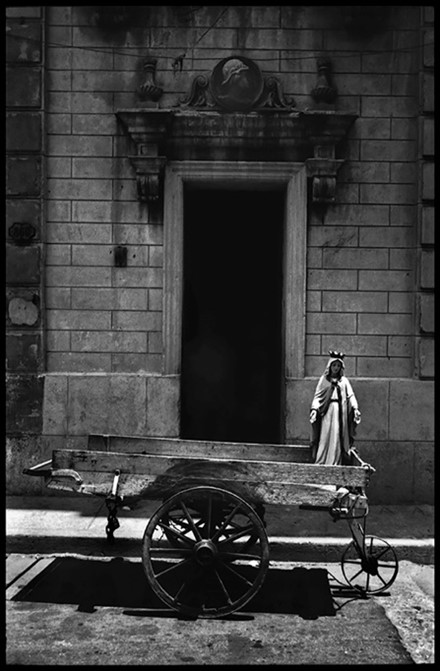

I don’t have the nerve to say that he was the one and only trailblazer, but he was one of them. In his work converged three aspects that built his signature: first, he was formed as a painter by Loló Soldevilla and as a graphic designer by Raúl Martínez, which gave him a very particular sense of composition. Second, he was able to integrate three photographic traditions: the Latin-American, the American, and the European. And third, but not least, he grew up wandering Havana’s streets, mataperreando. He knew every inch of the city, its core, as well as the core of the island (he traveled a lot from a very young age). Even his architecture photographs provide evidence of that deep relationship: his Havana, for example, is not Gasparini’s Havana. You will not find the wide, open, grandiloquent gaze, but closed, familiar frames. Minimal spaces doomed to the erosion of time, memory, and political malpractices.

In that sense, I could say that his importance for Cuban photography resides in the precious, intimate, and loving glance of what surrounded him. Perhaps that was the reason why he was invited to exhibit at “Cuba, 1933-1992, Two Visions: Walker Evans-Ramón Grandal,” a show that took place in Bordeaux, France, in 1992. Both [Evans and Grandal] offered a very personal conception of the island; both had the same kind of dialectic approach to reality. He always felt this invitation as one of his greatest achievements.

Finally, he never saw himself as an artist, and the reasons are hard to explain. Probably none of the old-fashioned photographers (and Papá was one of them) saw themselves as artists, but just as simple photographers. He used to make a joke about it, paraphrasing Susan Sontag: when photographers say they are not making art it is because they think they are doing something better.

EC: How did Grandal’s work evolve in subsequent periods in Cuba? And how did his work change once he moved from Cuba to Venezuela? What did his practice gain and/or lose?

KMG: As you know so well, the Special Period was a critical moment for Cuban people. Not just because of the obvious issues (famine, state repression, the rafter crisis), but because political crisis usually involves a rupture with/of a certain imagery, as well as the birth of a new one. Cuban visual arts were not the exception. They became more political, maybe not so openly dissident as they are today (as a spectator, you have to be aware of certain symbolic contents), but they were a seed. My father did not escape this tendency, he felt obliged to denounce and make a statement. That statement is the photographical essay El muro (The wall), the last work he did in Cuba before fleeing to Venezuela.

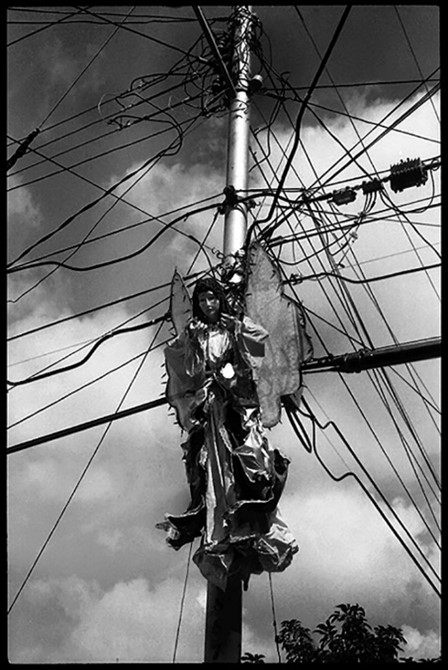

The images that integrate El muro were taken between 1991 and 1992, at the Havana seawall, el malecón. It could take years to define what that seawall means and why my father chose it as a subject. In the essay, you can trace a series of denounce marks: the graffiti that reminds the iron bars of a cell; the man riding a bicycle, “trapped” by a bunch of windows (dad used to call that photo “The thousand doors of Socialism,” meaning the idea of closed doors, the idea of asphyxia) or the emblematic “Cristo del malecón” (The Christ of the Seawall), that son who feels abandoned at the moment of crucifixion.

That was his “last” gaze to Cuba, in quotes because he returned to the country a few times after we left and took photos, of course, but in his Venezuelan way. Venezuela changed his conception of images. As he repeatedly said: he lost the interest on objective photography and began to express brief “opinions.” The subjects of these new images were the same: people, life in the streets, but his language became more obscure, probably because the fact of being an immigrant, of stepping into the unknown, forced him to look less for the outside and more for the inside.

EC: What would you consider to be Grandal’s most iconic photographs?

KMG: It is hard to say. It is like choosing between my favorite Beatles’ songs. To me, his daughter, “Las patas peludas” (The hairy legs) and “Los pajaritos de Calabozo” (The birds from Calabozo). But to the public, probably “La mano de Alfredito” (Alfredito’s hand, Alfredito meaning another renowned Cuban photographer, Alfredo Sarabia) and “El borracho de Choroní” (The drunk from Choroni). These are not titles, he did not title his photographs, but the essays or the series, his codes to identify these images.

EC: Talk to me about the process of going through his archives and work as you prepared to move his collection to the CHC. And what does it mean to you personally to have his work at the Collection?

KMG: I thought that going through his archives and letting them go would be distressful, but it was not. At least not as I believed (unexpectedly, answering to this interview was more moving, in a way). Of course, it was not easy to say goodbye to those tiny, crafted envelopes that had been part of my life since I was born, but the whole process was incredibly surprising and liberating. Surprising because it allowed me to rediscover my father’s magnificent work and to understand it as a whole; to find new connections between its series and languages. Also, to understand a lot of things about the person he was that probably I did not understand while he was alive. I feel proud of the photographer and proud of being his daughter. It was liberating because to carry on a legacy can be a heavy burden for someone who does not know or doesn’t have the mechanisms to take care of it. It opens a lot of questions about the future of that heritage.

I was first trained professionally as an art historian and later became a curator of photography in Venezuela, so I am fully aware of the importance of archives. Archives are living entities and they need to be in spaces that allow them a special kind of expansion. That is why it means a lot to me, to us, to have his work in the collection. It makes us happy. It is safe and accessible to students, researchers, and photographers, something that my father wanted. He loved knowledge, to acquire it, to spread it. And not give it just to any collection, but one that does an incredible job with Cuban culture, that he loved so much. It means that his work is currently in a place that transcends him and transcends us. We are grateful. He would be too.

Shortly after moving the archives to the collection, we scattered his ashes in the sea, at an incredibly beautiful point in Key West, in the same parallel of Havana. Everything that was left of his materiality (his work and his body) are now in magnificent places.