The Cuban Heritage Collection will be featuring highlights from Goizueta Fellows’ research investigations conducted during their fellowships. Claudia Suárez (@claudiasrz), shares the following about her research on ballet history during the Cold War:

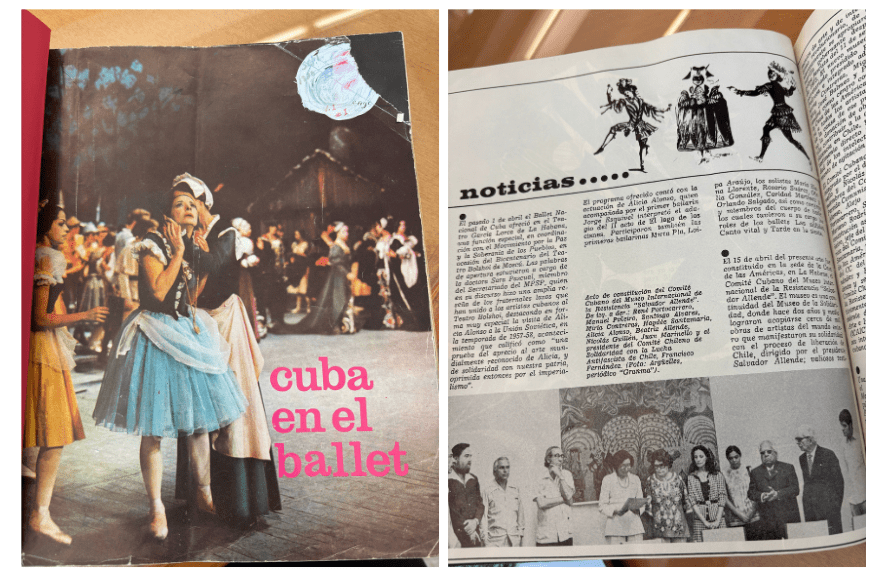

“Trataremos a la vez de recoger y divulgar no sólo nuestro movimiento de ballet nacional, sino otros esfuerzos dispersos de países hermanos de América Latina, que no han logrado aún romper el marco del subdesarrollo como lo ha hecho ya el nuestro que por ello puede hoy, legítimamente, hacer válido el nombre de esta revista: Cuba en el Ballet.”

– Angela Grau Imperatori, “Editorial,” Cuba en el Ballet, Volumen 1, Número 1, Septiembre de 1970.

I was 10 years old the first time I visited Cuba, and 13 the second time. I do not think that younger me was aware that those two trips to the Escuela Nacional de Ballet would be the inspiration for my PhD research. Fourteen years later, my archival experience at the Cuban Heritage Collection certainly felt like visiting Cuba (and beyond) for the third time. And I am convinced I sharpened the direction of my forthcoming historical narrative.

Young scholars of history are usually told that one cannot rely on the archive to answer all their research questions. Rather, one must come with an open mind: “you never know what you will find.” With my intention to study ballet dancers who deserted Cuba, as well as the Ballet Nacional de Cuba’s connections with the Soviet Bloc, I came to explore anything and everything the collection had about ballet, ballet companies, Soviet-Cuban relations, defectors, migration waves, and Cuban ballet in exile. And when it comes to the performing arts, press clippings, theater programs, and correspondence are the protagonists of one’s story.

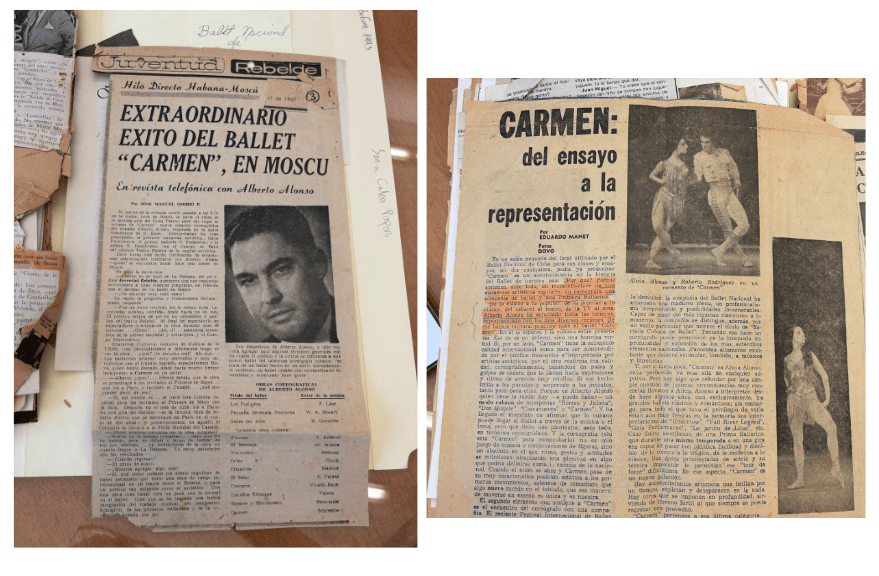

I started with the Alberto Alonso and Sonia Calero Papers. Being part of the Alonso trifecta, Alberto became an unexpected defector. This collection presented a rich history of his choreographic works in Cuba (and the Soviet Union) that were later, as other sources I found showed, not performed as much in the future. I was already seeing a clear narrative: Alberto and Sonia’s careers, both on the island in contrast to those in exile, are undoubtedly not uncommon for the rest of my historical characters.

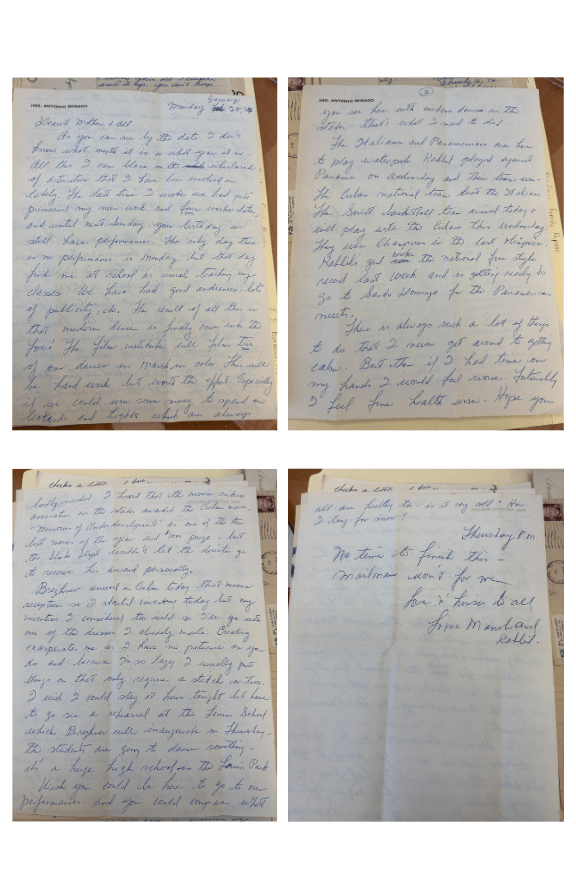

I shifted to finding further connections between the Cuban state and dancers. Lorna Burdsall, an American modern dancer, married none other than Manuel Piñeiro, the first head of Dirección General de Inteligencia of the Castro regime. The Burdsall Family Papers contains hundreds, perhaps thousands, of letters between Lorna and her family in the United States. Though one may take her complaints about Alicia Alonso’s ballet company always being more privileged, I started to conclude that modern dance was as connected to politics as I suspected it to be. Lorna Burdsall is the embodiment of this connection, and I found her references to the socialist bloc equally important to those I found in the ballet scene.

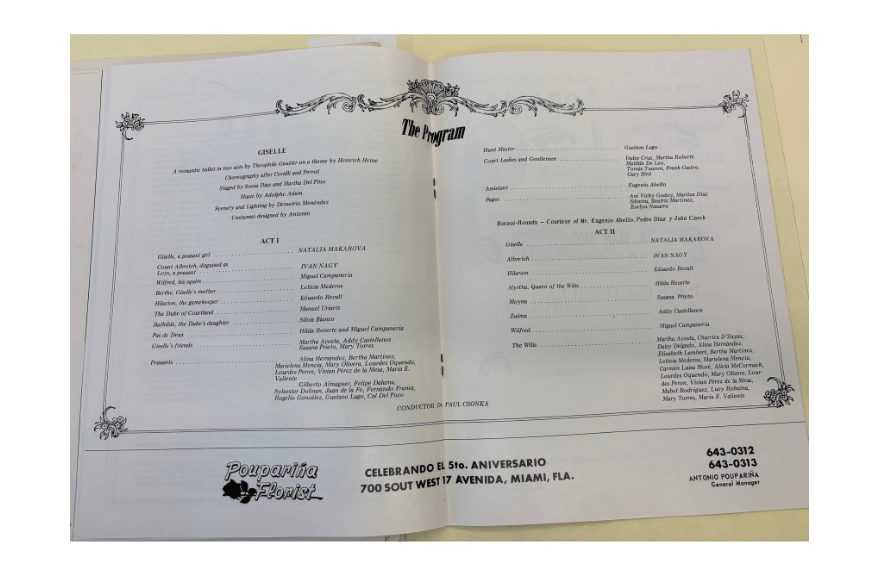

I recognize the work of many senior scholars before me who have studied the multiple migration waves of Cubans since 1959. My task of finding the artists within those migration waves sometimes feels like finding needles in multiple haystacks. However, the following collections were pivotal in my scavenger hunt: Ballet Concerto Collection, Norma Niurka Papers, Armando Álvarez Bravo Papers, INTAR Theater Records, Mariel (Revista) Papers, and the Theater Ephemera Collection. Taken together, I started to craft a history of the performing arts in Miami, as well as a history of the struggles to craft an artistic career in exile. I am convinced that Ballet Concerto’s programs (pictured here, too) will become central to my narrative: I found out that the founders of the ballet company, deserters themselves, invited the Soviet bloc’s defectors as guest dancers for their performances. For me, this is hitting the bullseye of ballet exiles from the socialist bloc supporting each other.

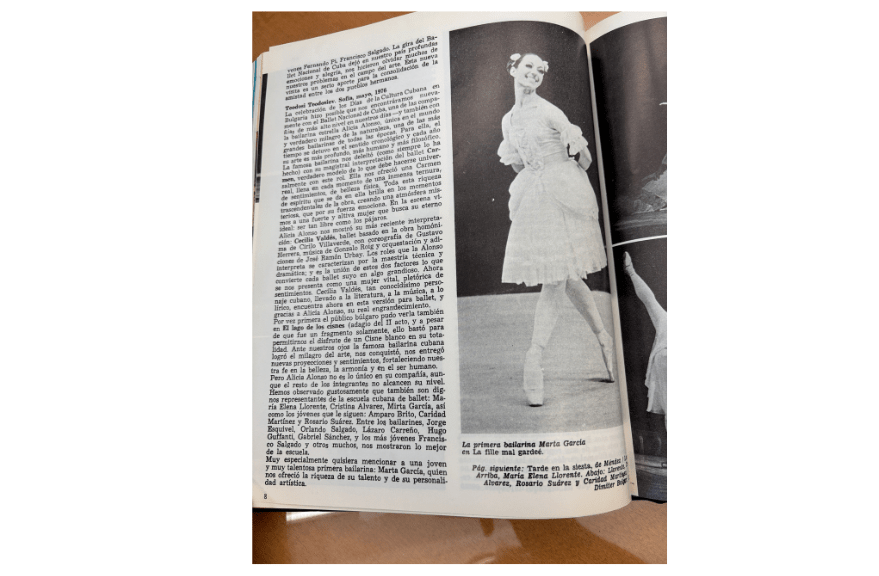

The highlight of my trip was thanks to Ms. Gladys Gómez-Rossié. After one of her wonderful Cuban cafecito breaks, Gladys found the entire collection of the revista Cuba en el Ballet for me. I had seen this magazine cited multiple times by the handful of scholars who study Cuban ballet history, but I thought I could only find its entire collection in Cuba. I spent a lot of time scanning every one of its issues. In it, I found connections with the socialist bloc, entire lists of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba’s international tour destinations (which included North Korea, Vietnam, and East Germany), snippets of critiques by socialist bloc’s journalists and art critics, among others. Most importantly, I witnessed the disappearance of dancers and choreographers from its issues once they deserted.

That little 10 and 13-year-old young dancer in me never imagined that I would be finding all those documents that illustrate the history she was so curious about all those years ago. I hope to give a new insight into the history of ballet, and I know that my dissertation project already has a new quality thanks to what I found at the Cuban Heritage Collection. It was the perfect place to start my research, and I look forward to continuing to come.