The Cuban Heritage Collection will be featuring highlights from Goizueta Fellows’ research investigations conducted during their fellowships. Bryan Guichardo (@westsidegriot), shares the following about his research on race, nationalism, and Black political thought during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the transnational Cuban context:

Neither do you know nor would you be able to imagine how hard it is for a black man to live in this North American land. In almost no convenient location are we allowed to rent, and when we are granted the favor, we are required to pay elevated rents. We are condemned to reside either in the tenant house, or too far north of the city, and the cost is expensive. Wanting to keep my family away from any dangerous frictions, I have had to pay expensive rents without having the means. It’s been a while since my situation went from bad to worse and I lack the strength. Only the glorious hope of a triumph for the Cuban cause keeps me going.

—Rafael Serra[1]

In 1890, Afro-Cuban activist and intellectual Rafael Serra, then living in exile in New York City, wrote to Tomás Estrada Palma—a leading figure in the Cuban exile movement, head of the Cuban Revolutionary Junta in New York, and future first president of the Cuban Republic—describing the harsh realities faced by Afro-Cuban exiles in the United States, particularly the pervasive anti-Black discrimination that made even basic necessities like affordable housing difficult to obtain. Serra was a central figure in both the Afro-Cuban community in New York and the broader Cuban independence movement. He worked alongside leaders such as José Martí, Sotero Figueroa, Juan Bonilla, and Francisco Gonzalo “Pachín” Marín, and was a key supporter of the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (PRC), founded in 1892. Through his organizing and activism, Serra worked to mobilize Afro-Cuban and working-class communities in support of the broader struggle for Cuban independence from Spanish colonial rule.

Beyond his nationalist commitments, Serra was deeply involved in racial uplift and Black diasporic organizing. In the early 1890s, he established mutual aid and educational programs for Afro-Caribbean migrants in New York. These efforts culminated in the founding of La Liga de Instrucción, a formal civic institution that became a vital center of intellectual and political life for Afro-Cuban and Afro-Puerto Rican exiles. Through La Liga, Serra and his allies promoted racial pride, anticolonial nationalism, and diasporic solidarity. In 1896, Serra also established the newspaper La Doctrina de Martí, which advanced Afro-Cuban rights, anti-racist critique, and revolutionary ideals. Through his writing and organizing, Serra linked the anti-colonial struggle in Cuba with broader currents of Black resistance in the United States, drawing from African American political thought, advocating for diasporic solidarity, and contributing to an emerging Afro-diasporic consciousness that extended beyond the Cuban exile community—efforts exemplified by his support for Afro-Cuban students at Tuskegee Institute.

My dissertation centers on the life and work of Rafael Serra y Montalvo (1858–1909), tracing his political thought, writings, and activism across the U.S. and Cuba. It examines how Serra drew from African American political discourse and racial uplift ideology to develop a vision of Afro-Cuban advancement rooted in both national liberation and hemispheric Black solidarity. By tracing Serra’s trajectory from exile in New York to his return to Cuba and his critical engagement with early republican politics, my project positions Serra as a key figure in reimagining race, citizenship, and Black intellectual life across Cuban nationalist politics and diasporic Black intellectual formations.

I applied to the Cuban Heritage Collection Pre-Prospectus Fellowship with the goal of contextualizing Rafael Serra’s intellectual and political trajectory within the broader currents of Cuban and diasporic Black history. Specifically, I sought materials related to the Cuban Wars of Independence, the U.S. occupations of Cuba, the early republican era, the dynamics of race relations between white and Black Cubans, and the development of Black political and intellectual thought. I began my research by reviewing collections related to these themes, including the Tomás Estrada Palma Collection, the Cordovés and Bolaños Families Collection, and the Historical and Literary Manuscripts Collection.

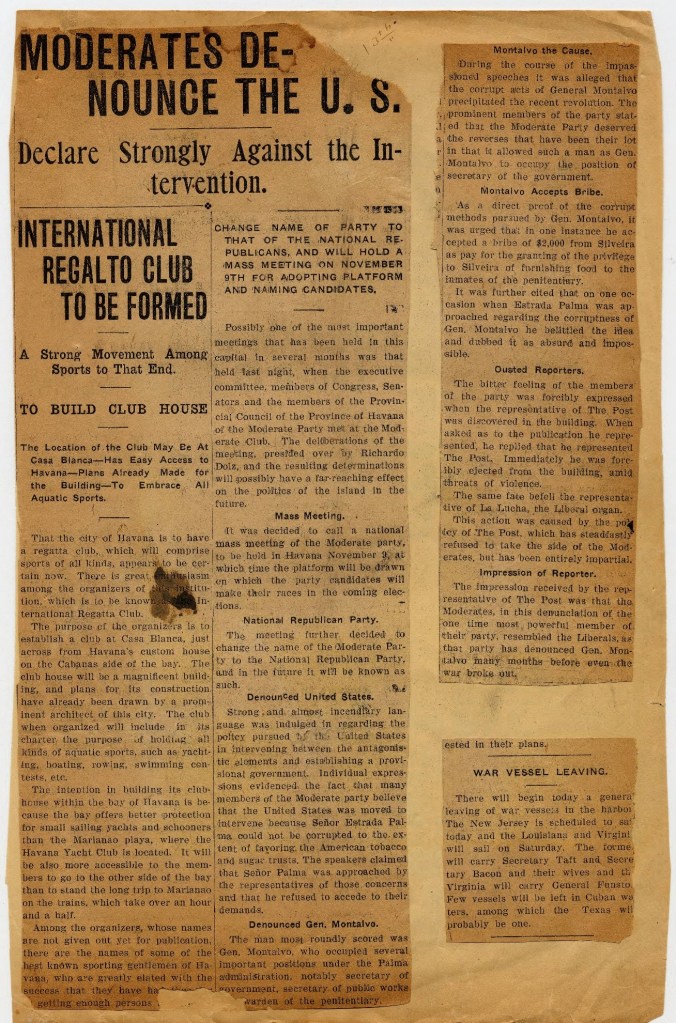

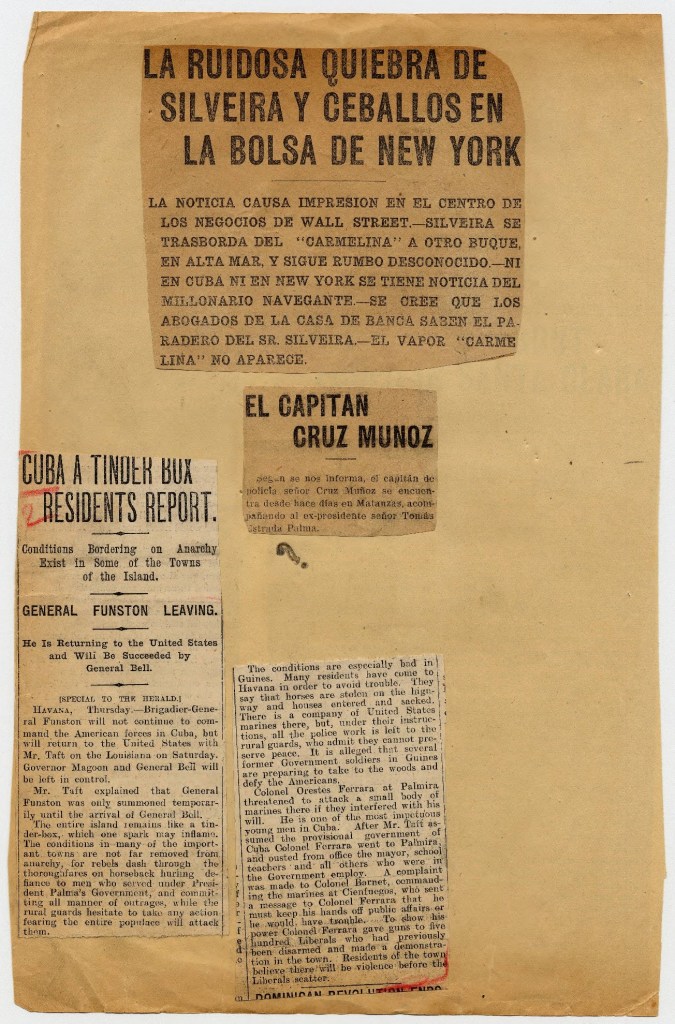

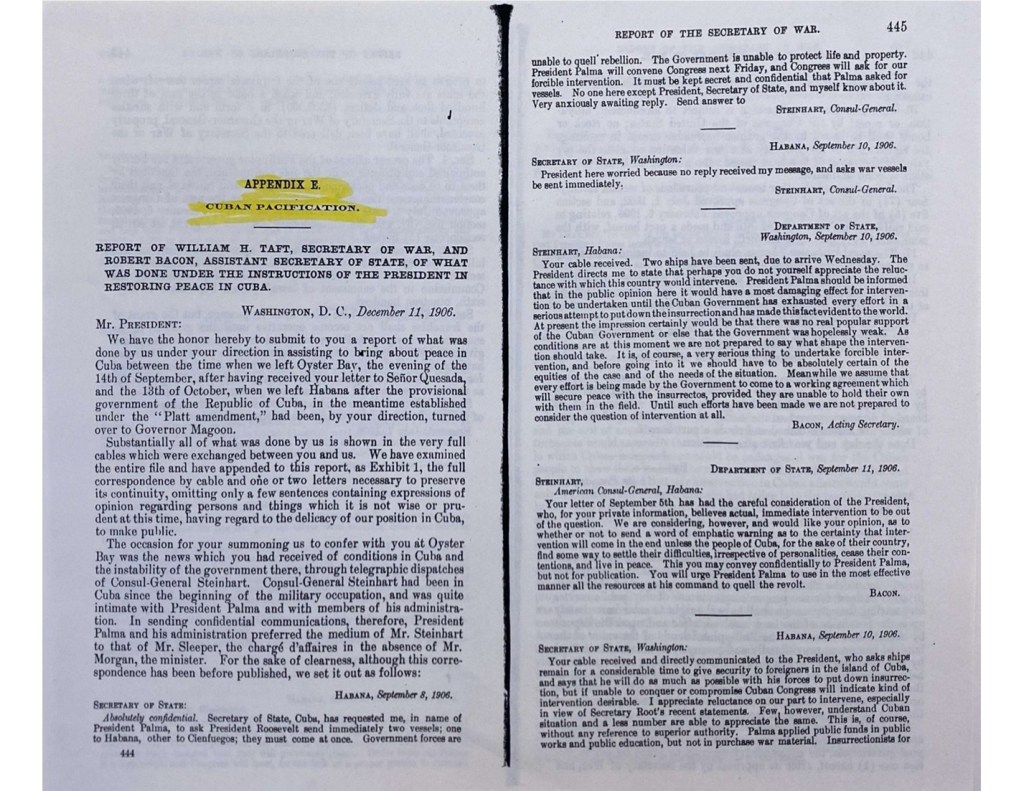

Although there were few explicit mentions of race or Afro-Cubans in many of these collections, they nonetheless provided valuable insight into the political and social contexts that shaped the experiences of Black Cubans during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Tomás Estrada Palma Collection was especially useful in helping me understand the dynamics of the second U.S. occupation of Cuba (1906–1909), a critical period during which Rafael Serra returned to the island and confronted the early challenges of republican life. Additionally, I discovered numerous significant letters in the Historical and Literary Manuscripts Collection, which included correspondence and photographs from key figures of the Cuban independence struggle, such as Máximo Gómez, Antonio Maceo, Tomás Estrada Palma, Juan Gualberto Gómez, and José Martí. These materials offered valuable insight into the broader networks and discourses that shaped the independence movement to which Serra was deeply connected, even when not directly referenced.

One of the most rewarding aspects of this fellowship was gaining access to rare, out-of-print Spanish-language books that are difficult, if not impossible, to find in New York. These included the works of scholars such as Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux, Tomás Fernández Robaina, Rafael Fermoselle, Pedro González Veranes, Serafín Portuondo Linares, Oilda Hevia Lanier, and Silvio Castro Fernández.[2] I also found several works directly related to Rafael Serra himself, including Pedro González Veranes’s Rafael Serra, patriota y revolucionario; fraternal amigo de Martí[3], and a rare copy of Serra’s own Ensayos políticos, segunda serie[4], which I thought I already owned but discovered was missing its first half. Another valuable find was José Martí: Obras completas, vol. 20: Epistolario[5], which includes personal and politically rich correspondence between Martí and Serra, as well as letters to other individuals in Martí’s social and political world. These letters offer a rare glimpse into the intimacy of their friendship and the mutual respect that shaped their collaboration. They are essential to understanding not only Serra’s political development but also the emotional and ideological ties that bound him to Martí and the broader Cuban independence movement.

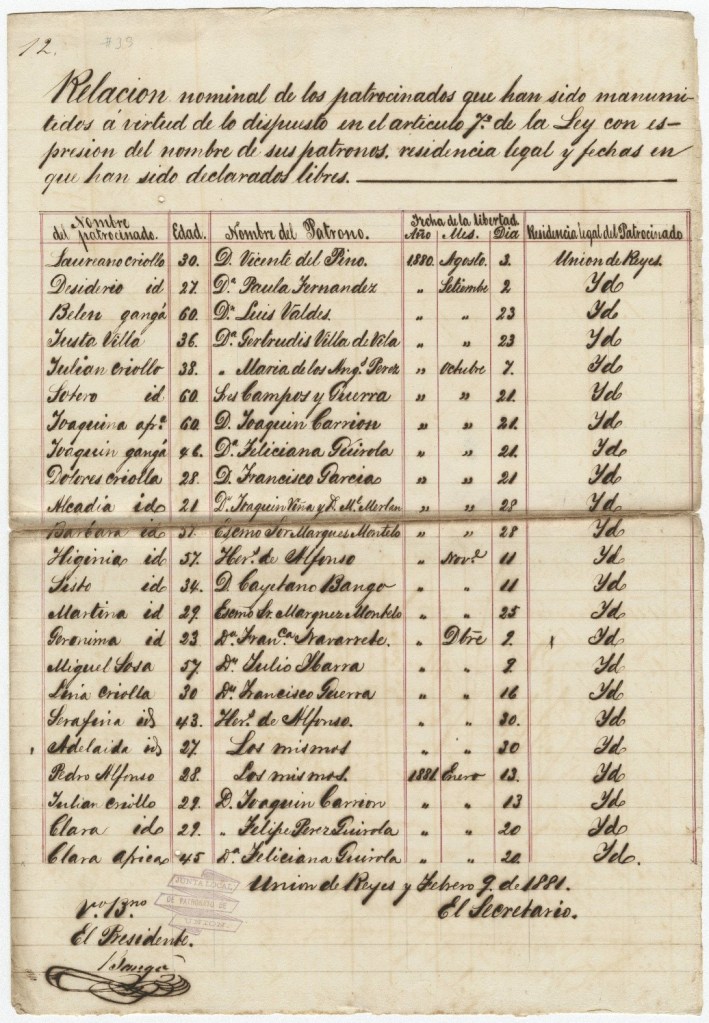

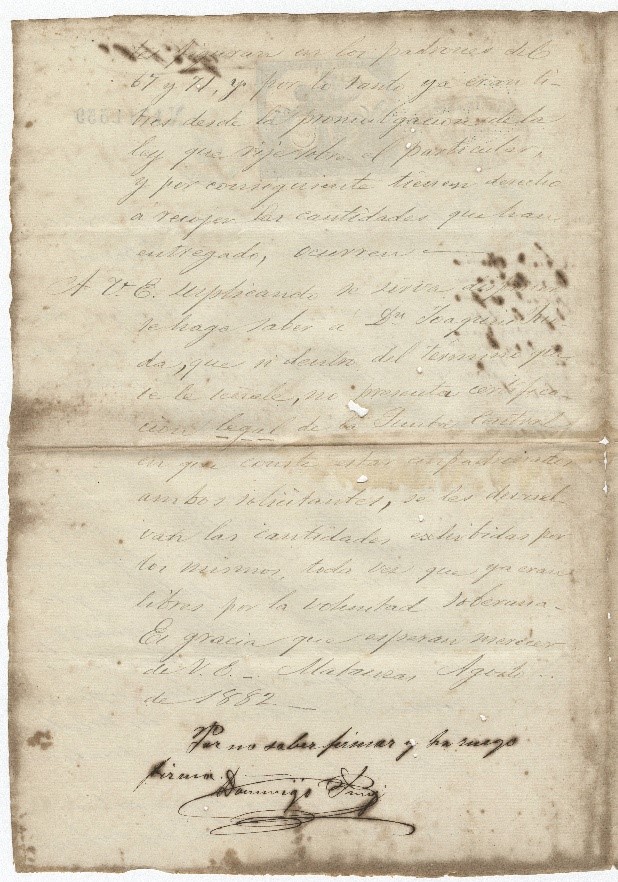

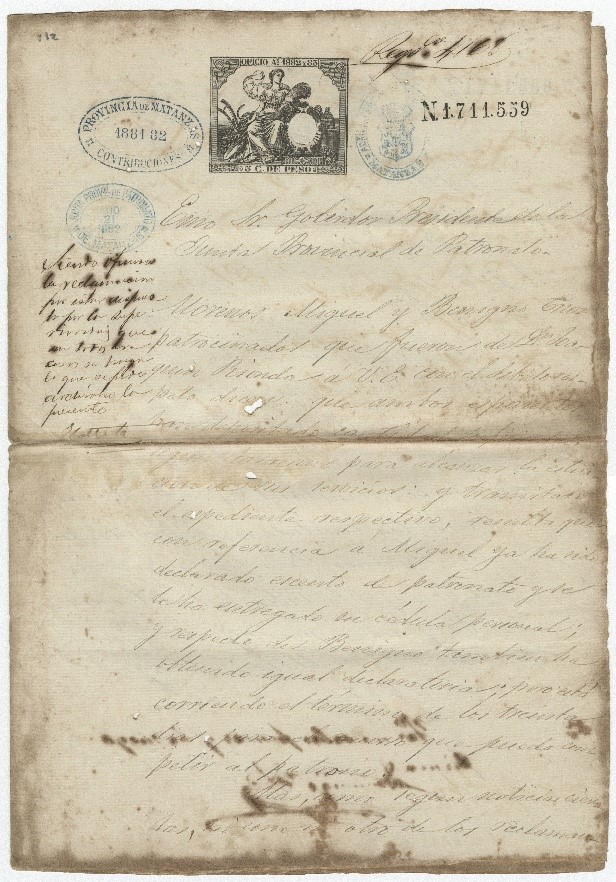

While on the fellowship, I also explored materials outside the exact timeframe of my proposed dissertation project—sources that, while unlikely to be incorporated into my current work, offered rich insight into adjacent topics and sparked ideas for potential future research. I reviewed the Junta Provincial de Patronato de Matanzas Records, which provided extensive documentation on Cuba’s transition from slavery to the patronato system. These included official letters granting freedom to formerly enslaved individuals (patrocinados), detailed administrative table of freed persons listing names and statuses, and correspondence regarding runaway patrocinados, all of which provided valuable context on the slow and contested dismantling of slavery in Cuba during the late 19th century.

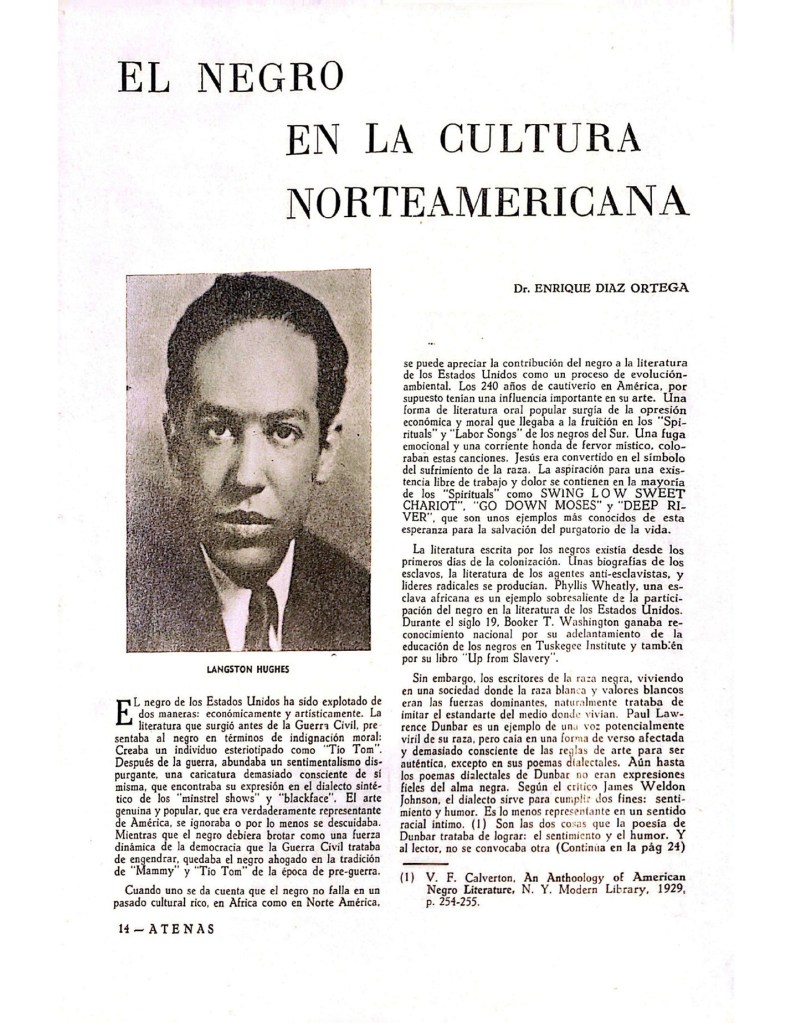

I also examined materials related to Club Atenas, one of the most prominent Afro-Cuban civic institutions of the 20th century. This included issues of its influential magazine, Atenas, which provided a vivid portrait of Afro-Cuban elite social life during the republic. The magazine featured articles on prominent African Americans, such as Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, short biographical sketches of key Cuban historical figures, and writings by Afro-Cuban intellectuals, including Juan René Betancourt. In addition to the magazine, I reviewed a set of illuminating conference papers organized by Club Atenas under the title Conferencias de orientación ciudadana[6]. These covered major political and social themes of the time—including political parties, immigration, economy, labor, education, discrimination, and the constitutional assembly—offering a powerful snapshot of how Afro-Cuban thinkers engaged national debates and claimed space within civic life in the republic.

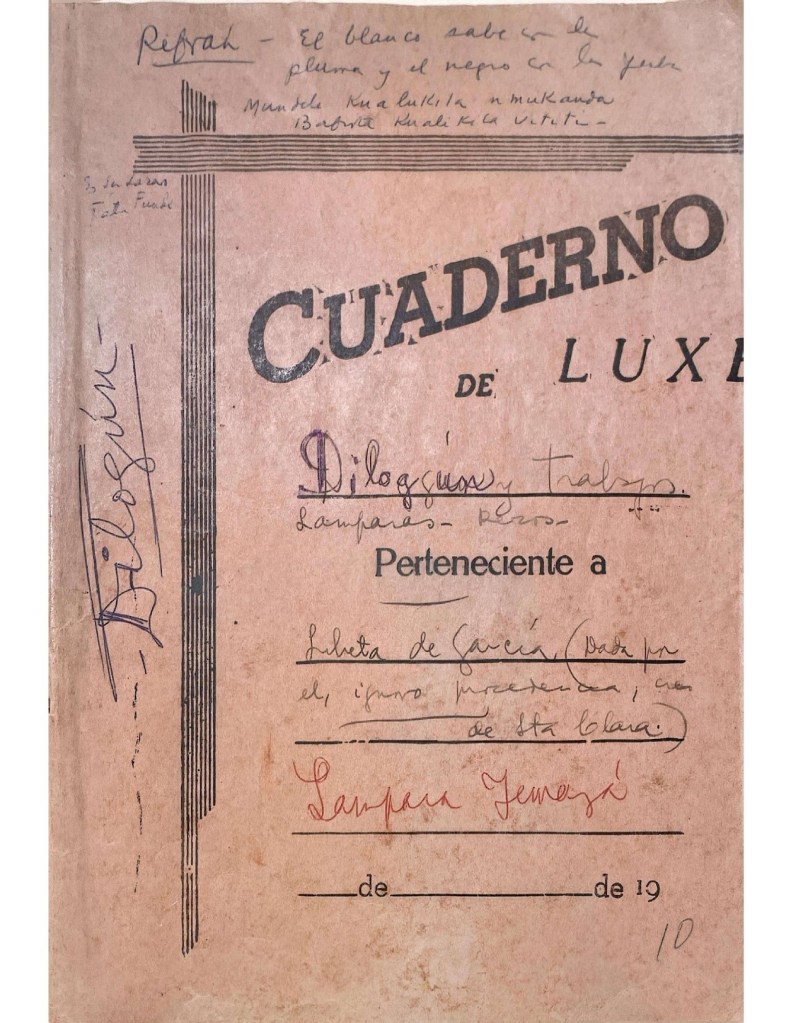

Additionally, I spent time with selections from the Lydia Cabrera collection, which—though outside the chronological and thematic scope of my dissertation—offered compelling materials on Afro-Cuban spirituality and cultural life. Among the most rare and notable finds were “Notas sobre África, la negritud, y la actual poesía Yoruba,”[7] and a libreta, a spiritual notebook belonging to one of Cabrera’s informants, used to record patakís (Yoruba sacred stories) and other elements of Lucumí religious knowledge. These items offered a powerful glimpse into the preservation and documentation of African-derived epistemologies in Cuba.

My time at the Cuban Heritage Collection was invaluable, not only for the sources it provided but for the intellectual clarity and inspiration it added to my ongoing dissertation research. The materials I consulted enriched my understanding of Rafael Serra’s intellectual and political world, helping to situate his activism within the broader currents of Cuban and diasporic Black political thought. I leave the CHC with a renewed sense of direction and purpose, grateful for the opportunity to engage with such a rich and thoughtfully preserved archive.

[1] Rafael Serra, letter to Tomás Estrada Palma, 1890, quoted in José I. Fusté, Possible Republics: Tracing the “Entanglements” of Race and Nation in Afro-Latina/o Caribbean Thought and Activism, 1870–1930 (PhD diss., University of California, San Diego, 2012), 110. Translation by Fusté of the original letter cited in Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux, Rafael Serra y Montalvo: Obrero Incansable de Nuestra Independencia (Havana: Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba, 1975), 148.

[2] Pedro Deschamps Chapeaux, El negro en la economía habanera del siglo XIX (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1971); Tomás Fernández Robaina, El negro en Cuba, 1902–1958: Apuntes para la historia de la lucha contra la discriminación racial (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1990); Serafín Portuondo Linares, Los Independientes de Color (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1960); Oilda Hevia Lanier, El Directorio Central de las Sociedades Negras de Cuba (1886–1894) (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2000); Silvio Castro Fernández, La masacre de los Independientes de Color en 1912 (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2001).

[3] Pedro González Veranes, Rafael Serra, patriota y revolucionario; fraternal amigo de Martí (La Habana: Oficina del Historiador de La Habana, 1959).

[4] Rafael Serra, Ensayos políticos, segunda serie (New York: Imprenta de P. J. Díaz, 1896).

[5] José Martí, Obras completas, vol. 20: Epistolario (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1991).

[6] Club Atenas, Conferencias de Orientación Ciudadana: Los Partidos Políticos y la Asamblea Constituyente. La Habana: El Club, 1939.

[7] Lydia Cabrera, “Notas sobre África, la negritud, y la actual poesía Yoruba” Revista de la Universidad Complutense 24, no. 95 (1975): 9–58.

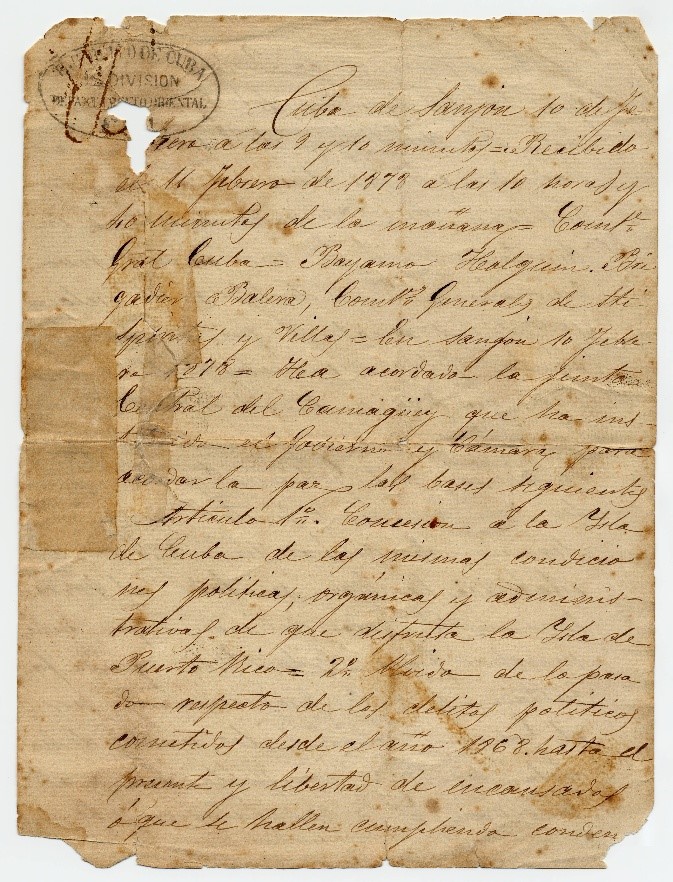

Extract of the Treaty of Zanjón, February 1878. This document marks the formal end of the Ten Years’ War (1868–1878), the first major Cuban independence struggle against Spain. While the treaty failed to grant full independence or abolish slavery, it offered limited political reforms and a conditional amnesty to Cuban rebels. Many Afro-Cuban and pro-independence leaders, including Antonio Maceo, rejected its terms, highlighting the racial and political tensions that would continue into future liberation efforts. Source: Cordovés and Bolaños Families Collection, CHC0398, Series I, Sub-series B, Box 1, Folder 16. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries.

Letter from José Martí to Máximo Gómez, December 2, 1894. In this letter, written from New York, Martí tells General Gómez that he is awaiting his orders and expresses admiration for the courage and capability of all Cubans, both on the island and in exile. Source: Cuban Historical and Literary Manuscript Collection, CHC0347, Box 6, Folder 6. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries.

Source: José Martí, Obras completas, vol. 20: Epistolario (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1991), 344–347.

Document on Behalf of Miguel and Benigno Cruz, August 1882. Official letter submitted on behalf of patrocinados Miguel and Benigno Cruz, in which they claim to have fulfilled the financial requirement necessary to terminate their status under the patronato system. Source: Junta Provincial de Patronato de Matanzas Records, CHC5298, Box 1, Folder 47. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries.