For Culinary History Month, current fellow in residence, Allyson Pérez, Ph.D. student at University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, shares the following about some of her research findings so far in the archives. Pérez’s dissertation project seeks to document Cuban restaurants in the United States throughout time and understand how community, identity, and politics are reflected in these spaces.

Throughout the history of the United States, restaurants have served important functions in immigrant communities as places to reminisce about home, forge communal bonds, and spur economic growth. In this regard, the Cuban community of South Florida is no exception, and in fact, restaurants are one of many factors that have led to the triumphant success story that is Miami’s Cuban American community. As Cubans continued to arrive in South Florida after Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution, the community’s entrepreneurial spirit has helped reshape Miami in their own image. Between 1967 and 1976, the number of Cuban-owned businesses in Miami increased by over 700 percent, from 919 in 1967 to around 8,000 in 1976, numbers that have only continued to increase in succeeding decades. While the nature and size of these businesses vary, Portes and Wilson note that restaurants are particularly popular among smaller entrepreneurs.[1]

Clearly, then, restaurants have played a special role in the story of Cuban Miami’s rise. However, despite this fact, little academic research has been published about Miami’s Cuban restaurants, an oversight I seek to correct with my research, and that I am grateful to the Cuban Heritage Collection and Goizueta Graduate Fellowship for allowing me to explore this summer.

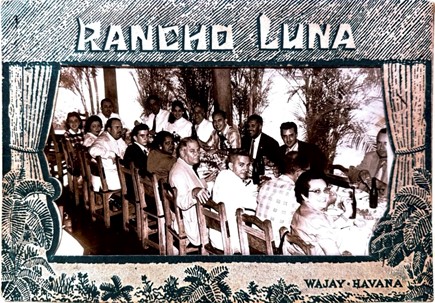

Many Cubans who settled in Miami after the revolution came from Havana, a city with a vibrant restaurant culture of its own that, in many ways, set the tone for Miami’s future Cuban restaurant scene. Dining out in 1940s and 50s Havana was an event, full of glitz and spectacle, both for tourists and the local Cuban population. Many restaurants in the city offered souvenir photo services to their guests, several of which can be found in the CHC’s archives, including from the restaurants Sans Souci and Rancho Luna. In these photos, guests are dressed to the nines, in large groups of family and/or friends, smiling and chatting pre- or mid-meal as the photographer made their way around the dining room filled with white tablecloth-clad tables.

Images: Sans Souci souvenir cover and photo (Restaurant Ephemera Collection, Box 1)

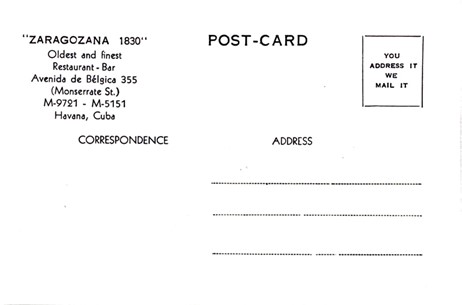

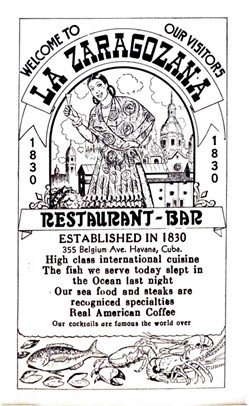

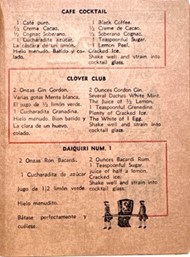

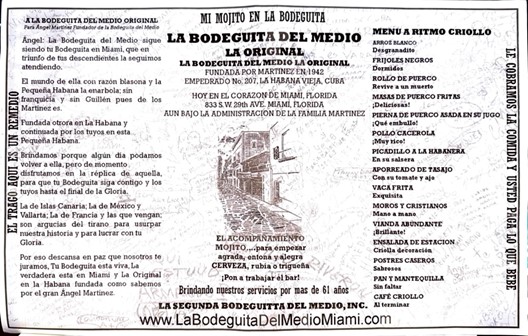

Among notable Havana restaurants whose ephemera can be found in the Collection is La Zaragozana, Havana’s oldest restaurant, founded in 1830, which specialized in seafood, catered to a tourist clientele and advertised in English (see postcard). Two other restaurants made famous by the patronage of Ernest Hemingway, La Bodeguita del Medio and Bar La Florida (also known as El Floridita), can also be found in the Collection, and were popular among tourists and locals alike: La Bodeguita for its home-style food and mojitos and Floridita for its mixed drinks, including its famous Daiquiri.

Images: La Zaragozana postcard, front and back (Guillermo “Willy” González Collection, Box 6)

Images: Bar Florida Havana Cocktail Menu, Cover, Daiquirí Pages (Restaurant Ephemera Collection, Box 1)

After the revolution, as Cubans made their way across the Florida Straight to Miami, many of these popular Havana restaurants moved with them, including La Bodeguita del Medio, Floridita, La Zaragozana, Rancho Luna, and others, setting up shop on S.W. Eighth Street, or Calle Ocho, in what we know now as Little Havana. While restaurant ownership and staff may have made their way to Miami, the physical buildings in Havana themselves often remained restaurants owned and run by the Cuban government, which led to stand-offs between the restaurants in exile and those located in their original buildings in Cuba. Menus from Floridita and La Bodeguita Miami advertise these moves and reopenings to their customers, claiming authenticity for themselves as the Cuban government continues to operate the original restaurants in Havana.

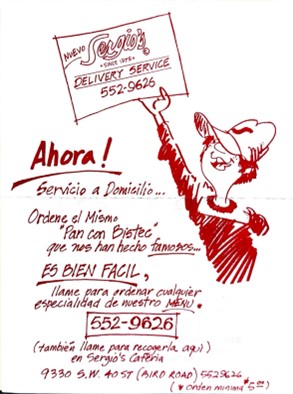

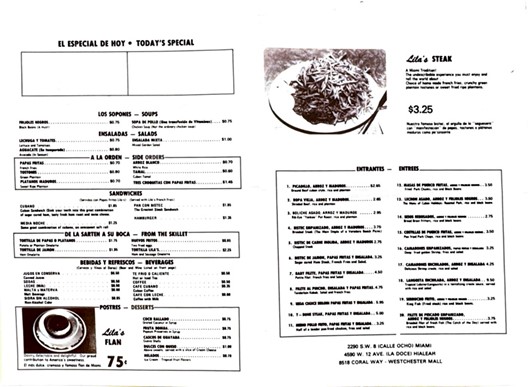

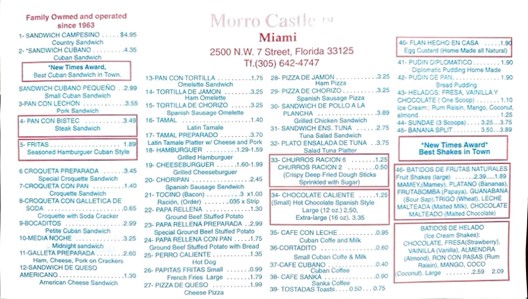

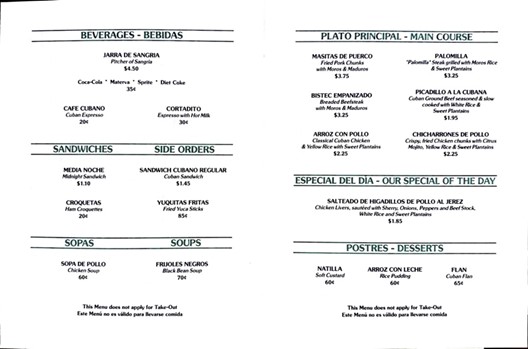

Heritage restaurants from Havana are not the only Cuban restaurants that made it in South Florida—the boom of Cuban Miami’s “ethnic enclave” in the 1970s saw the birth of many new restaurants that people may recognize today, including the internationally popular Versailles, La Carreta, and Sergio’s, as well as other popular places that have since closed their doors but live on in local legend, like Lila’s (renowned for their famous steaks covered in a mountain of freshly cut French fries) and the original Morro Castle on Calle Ocho (although you can still enjoy the same food at their Hialeah location).

These restaurants’ menus housed in the Cuban Heritage Collection come from a bygone era where you could buy a cortadito and a croqueta for 50 cents, and a Cuban sandwich for $1.45, as Versailles offered its customers when it opened back in 1971, and which was available again for one day only back in 2001 when they celebrated their 30th anniversary. Nonetheless, it is a fun trip down memory lane to remember all the good times spent with family and friends at the table over delicious Cuban meals in a city so many of us are proud to now call home.

[1] Wilson, Kenneth, and Alejandro Portes. “Immigrant Enclaves: An Analysis of the Labor Market Experiences of Cubans in Miami.” American Journal of Sociology 86, no. 2 (1980): 295–319. p. 304.