The Cuban Heritage Collection will be featuring highlights from Goizueta Fellows’ research investigations conducted during their fellowships. Daniel Delgado, shares the following about his research on the experiences of Black Caribbean and Chinese migrant workers and their impact on the Cuban sugar industry in the early 20th century:

𝘜𝘯𝘧𝘪𝘯𝘪𝘴𝘩𝘦𝘥 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘦𝘥𝘰𝘮𝘴: 𝘚𝘶𝘨𝘢𝘳 𝘙𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘯𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘶𝘤𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘙𝘢𝘥𝘪𝘤𝘢𝘭 𝘚𝘰𝘭𝘪𝘥𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘺 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘌𝘢𝘳𝘭𝘺 𝘊𝘶𝘣𝘢𝘯 𝘙𝘦𝘱𝘶𝘣𝘭𝘪𝘤

Dr. Ramiro Cabrera recounts the history of sugar cultivation and production throughout centuries in Cuba, mostly under colonial rule, in the essay “La Industria Azucarera,” published in 1925 in El Libro de Cuba. Writing three decades after the 1895 war of Cuban independence as the Secretario de la Sociedad de Hacendados y Colonos, Cabrera explains that during the fight against Spain, destructive fires swept Cuba’s countryside and left only a few isolated factories and sugar mills with minimal productive capacities, nearly resulting in the total ruin of the sugar industry.[1] However, the sugar industry exploded to unprecedented proportions when U.S. investors poured money into the establishment of large-scale sugar mills largely located in the Camagüey and Oriente provinces of eastern Cuba.[2] In just over twenty years (1903-1925), sugar production quintupled, exceeding five million tons. This would not have been possible were it not for the contributions of immigrants who moved to Cuba to work in a wide variety of trades and occupations that were central to the sugar economy.[3]

Although the main source of migration to Cuba was Spain, migrants also arrived on Cuban soil from neighboring Haiti, Jamaica and other British possessions in the Antillean archipelago. Black Caribbean braceros made the most vital contribution to the reconstruction of Cuba’s sugar industry as poorly paid cane cutters in grueling conditions.[4] To know more about these workers, I scoured through large boxes full of letters, maps, annual reports, title deeds, financial statements, and related documents of the Guantánamo Sugar Company. Besides repeated findings of company executives complaining about labor shortages, rumors of strikes and uprisings, or the need to import more workers, my search in the company’s boxes also generated an understanding of the investment logics of early 20th century sugar production.

As the company records evidence, executives believed that major investments in railroads, port drainage, sugar processing machinery, and roads would provide benefits to their efforts to make the most of the island’s agricultural capacities. However, to make the investments profitable, the Guantánamo Sugar Company and others like it, depended on “a sufficient and steady supply of cane to keep the mills going… without plenty of cheap cane… sugar factories, however well managed, cannot long compete.”[5] This drove sugar companies to seek out more land and workers to cultivate and cut sugar cane, coming to rely, as Cabrera points out in his essay, on “innumerables negros trabajadores de Jamaica y Haití” who they paid nearly nothing.[6] In fact, during a 1956 congressional hearing held before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Laurence A. Crosby, the then-chairman of the US-Cuban Sugar Council, admitted that “the wage for an agricultural worker… would be about $3 a day.”[7]

Caribbean braceros working on sugar plantations found themselves at the bottom of a hierarchy of occupation in the sugar industrial complex, and company-enforced segregation of workers reinforced racial and social inequalities. Immigrants from Spain tended to work in construction, on the railroads, and in the boiler rooms. Immigrants from the British, French, and Dutch Caribbean islands worked in the fields. Chinese immigrants worked in the mill’s centrifugal department. While this sometimes generated disunity and conflict, class-conscious labor struggles improved bonds of fraternity and solidarity among Cuba’s workers in efforts to catalyze political change and genuine democracy, sovereignty, and racial equality. Shared experiences of exploitation, dislocation, and dispossession could be the basis for collective action to improve working conditions if workers organized their collective power across difference.

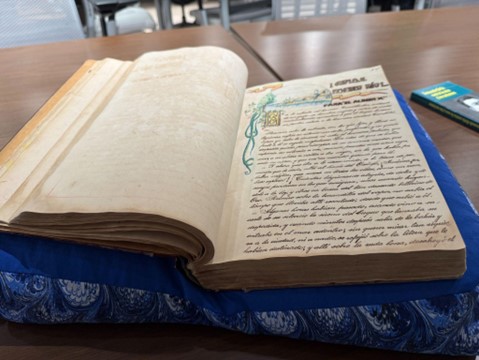

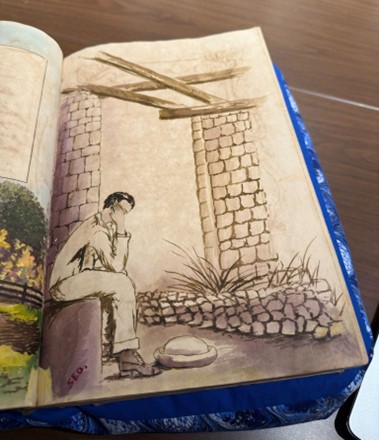

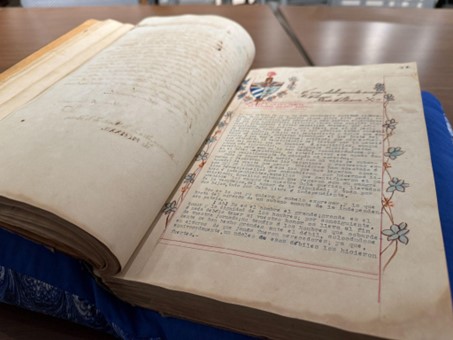

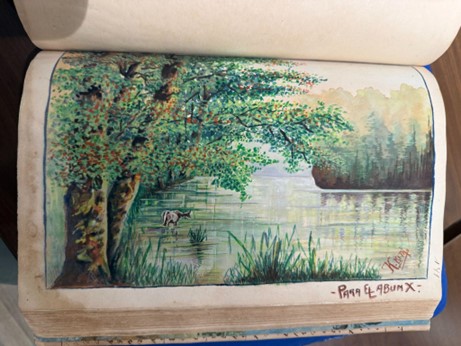

In addition to national, ideological, and linguistic differences, workers faced violent repression of their efforts to organize. Police brutally cracked down on striking port workers, railway workers, and sugar mill workers during the early 20th century, leading to arrests, death, and injury. As one special source from the early 1920s illuminated, diverse sectors of working people within Cuban territory ended up in prison. Compiled by a Chinese-Cuban by the name of Francisco Alonso, Album “X” collects contributions from prisoners held in Castillo del Príncipe in Havana as “un recuerdo de aquellos compañeros que sufrieron y compartieron conmigo, los momentos más tristes de la vida.”

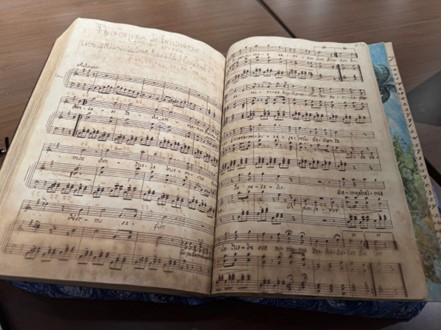

The album entries reveal a breadth of linguistic diversity and national identity, as well as a rich variety of forms of expression. Inmates from places like Mexico, China, Spain, Haiti, and Cuba contributed to Alonso’s album with poems, philosophical essays, political treatises, music compositions, colorful paintings, autographs, and simple messages of friendship and camaraderie. Described by Alonso as a “luz esplendorosa en las penumbras de la prisión,” the album and the prisoners’ participation in its creation manifested a collective act of inscription as peaceful defiance to “quienes nos repulsan y nos condenan.” In finding this sense of shared humanity in “la Mansión de los infortunios,” the name many chose for the prison, the prisoners challenged the intention to isolate and deprive prisoners of their freedom. In the eyes of Alonso, this brought the prisoners “más cerca… del perfecto ideal de fraternidad” than those on the outside of the institution’s walls. The album’s display of diversity is a testament to the movement of people across borders and seas throughout the world during the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries, when many passed through or settled in Cuba. The Latin phrase that serves as subtitle to this album, rari nantes in gurgite vasto, translates to “rare survivors in the immense sea,” a sentiment that captures both the feeling of prisoner isolation and the basis of a bond: survival.

As Cuba transitioned from colony to republic after the independence wars, renewed sugar production transformed its landscape and economy—this time on the basis of free labor and not slavery, as a modern nation and not a colony. The influx of North American capital toward the purchase of large portions of arable land, the practice of deforestation to make way for immense plantations, and the trafficking of laborers to cut cane, build railroads, and transport goods drove the transformation. However, Alonso’s radical project of recording and remembering the diverse experiences and creativity harbored in forgotten spaces of unfree sociality offers a register for reckoning with the human and environmental costs of Cuba’s expeditious reconstruction of the sugar industry during the early republic. As the politically conscious and socially critical writings found in Album “X” affirm, while the republic marked a new period of freedom from Spanish colonialism, freedom remained contingent and its meaning was unstable, especially for migrant workers, political radicals, the poor, and those living outside the norm (and inside a prison).

[1] Ramiro Cabrera, “La Industria Azucarera,” El Libro de Cuba: Historia, Letras, Artes, Ciencias, Agricultura, Industria, Comercio, Bellezas Naturales (Obra de Propaganda Nacional, La Habana, República de Cuba, 1925). The historian Gillian McGillivray explains that the burning of cane fields was a sign of internal labor negotiations during times of peace and also a dominant form of political civil warfare during the revolutions and rebellions of Cuba’s nineteenth century and twentieth. In this way, “burning cane functioned as a means of imposing the colonos’ or workers’ will over mill owners, as a means of protest.” In the context of the independence wars of 1868-1879 and 1895-1898, the cane burnings were instigated by leaders who aimed to destroy the social and political system sustaining Spanish colonialism. See: McGillivray, Blazing Cane: Sugar Communities, Class, and State Formation in Cuba, 1868–1959 (Duke University Press, 2009), 4-5.

[2] Yurisay Pérez Nakao, Inmigración española, jamaicana y árabe a Banes: Historia, cultura y tradiciones (Ediciones Holguín, 2008), 9; Yurisay Pérez Nakao, La inmigración jamaicana en Banes (Ediciones Holguín, 2022), 18.

[3] Oscar Zanetti, “Los braceros jamaicanos en la industria azucarera cubana: el caso de la United Fruit Company,” en Migraciones antillanas: Trabajo, desigualdad y xenofobia, eds. Jorge E. Elías-Caro y Consuelo Naranjo Orovio (Santa Marta: Editorial Unimagdalena, 2021), 23.

[4] Rolando Álvarez Estévez, Azúcar e inmigración, 1900-1940 (Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1988).

[5] Memorandum in Re: Proposed New Factory, February/March 1915; Report of Observations signed by William Moore Carson and George R. Bunker, March 23-30 and April 4-8, 1915. Guantánamo Sugar Company records,Box 24, Cuban Heritage Collection.

[6] Cabrera, “La Industria Azucarera,” El Libro de Cuba, 717.

[7] Copy of US Senate Report of Proceedings, Hearing Held Before Committee on Finance, H.R. 7030, Statement of Laurence A. Crosby, President, Cuban-Atlantic Sugar Company and Chairman, United States Cuban Sugar Council. January 17, 1956, Washington, DC. Guantánamo Sugar Company records, Box 23, Cuban Heritage Collection.

Images of Album “X”: rari nantis in gurgite vasto (1922-1923). University of Miami, Cuban Heritage Collection, Cuban Historical and Literary Manuscript Collection, CHC0347, Box No. 21, Folder No. 1.