The Cuban Heritage Collection will be featuring highlights from Goizueta Fellows’ research investigations conducted during their fellowships. Hélio Augusto de Souza Alves, shares the following about his research on official state narratives and political and economic reforms in Cuba from the 1970s to the 1990s.

In the summer of 2022, I had the opportunity to conduct pre-prospectus research at the Cuban Heritage Collection with the support of the Goizueta Pre-Prospectus Fellowship. At the time, I not only immersed myself in the many documents the CHC has but also in the many research possibilities they offered to a then first-year Ph.D. student. Now, as a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate, I had the joy of returning to the very same archive that had welcomed me years before—this time with a better-structured, well-defined topic and more research experience.

As a Goizueta Research Fellow, in the fall of 2025 I revisited several collections I had consulted before and also examined new ones within the scope of my dissertation project, titled I Am the Revolution: Reforms, Reversals, and Contradictions in Communist Cuba, 1970–1994. This research—which stems, to a great extent, from my pre-prospectus work in 2022—examines the policy shifts and ideological contradictions of the Cuban Revolution between the 1970s and the 1990s, an era long overshadowed by scholarship that disproportionately focuses on the Revolution’s first decade. I analyze how Cubans perceived, navigated, and responded to these transformations, as well as the futures they envisioned within them. By examining shadow policymaking in Cuba that preceded the fall of the Soviet Union, my work reveals that changes systematized in the 1990s as supposed responses to the Special Period had been in the making decades earlier as reactions not to external political conjuncture but to popular demands and internal pressures. In doing so, my research also illuminates popular reactions and perceptions when state reforms diverged from the official narrative.

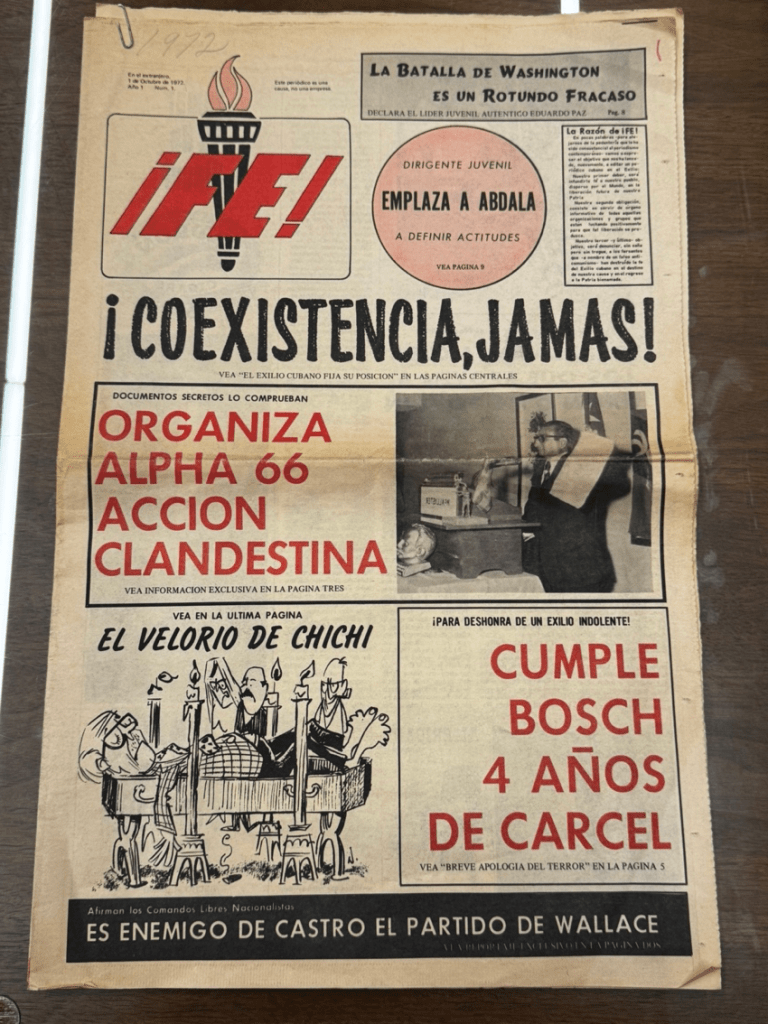

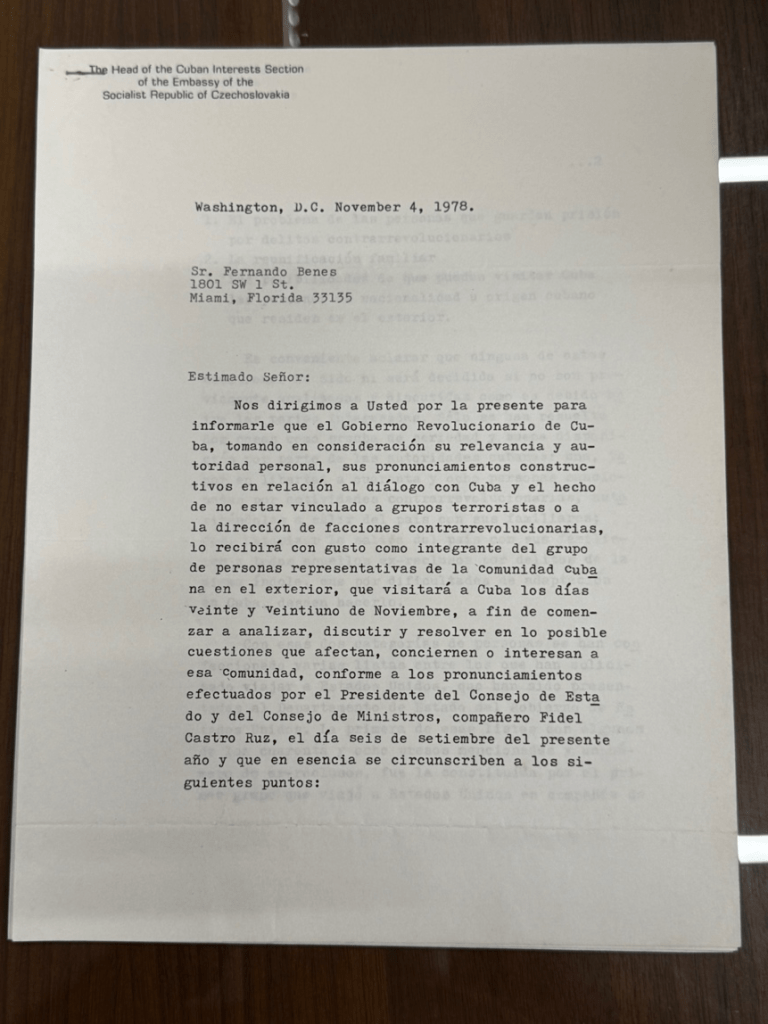

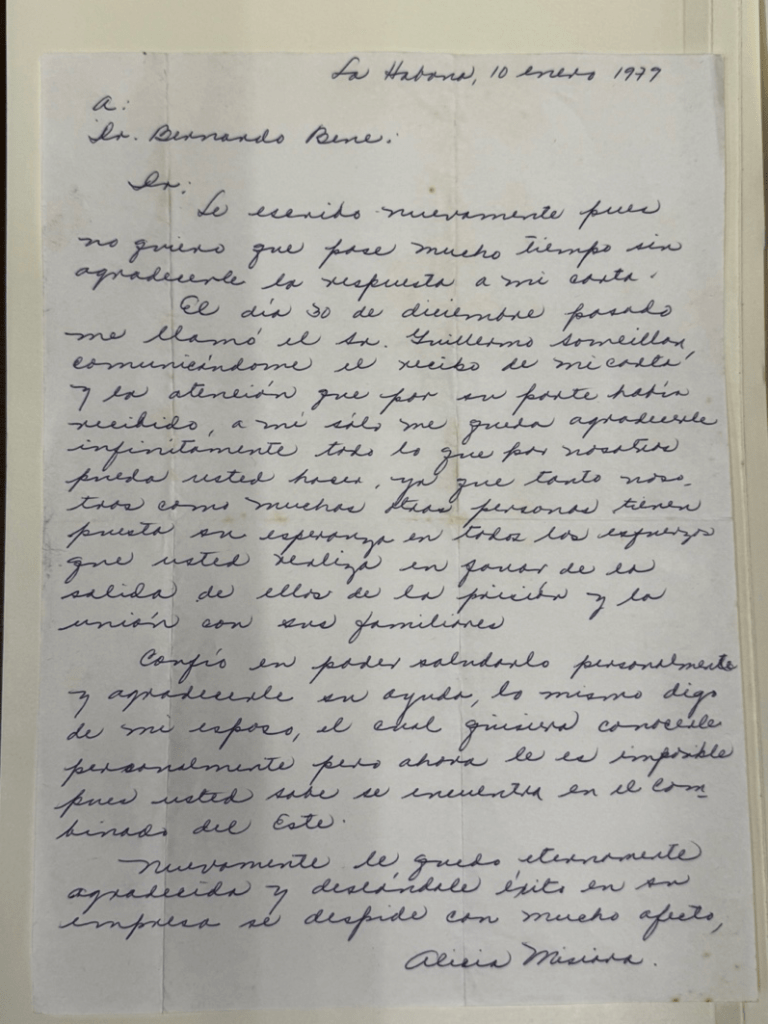

Over the course of two months, from Monday through Friday, I consistently examined many collections, newspapers, books, posters, and letters containing information on different aspects crucial to my research. Among the most interesting materials, I must highlight my findings in the Bernardo Benes Collection, which included communications with Cuban diplomats in the United States about negotiations between Havana and Miami, as well as letters from Cubans on the island requesting support for their travel to the United States in the context of The Dialogue in the 1970s. Moreover, the newspaper Fé!, directed by Carlos Rivero Collado, offered important insights into my work regarding the use of individuals and mass communication strategies as part of the Cuban regime’s intelligence and actions abroad. Through Fé! I found what I argue were intelligence reports by Cuban agent in Miami Carlos Rivero Collado and early evidence of strategies to destabilize the exile community from within.

Fé! October 1, 1972.

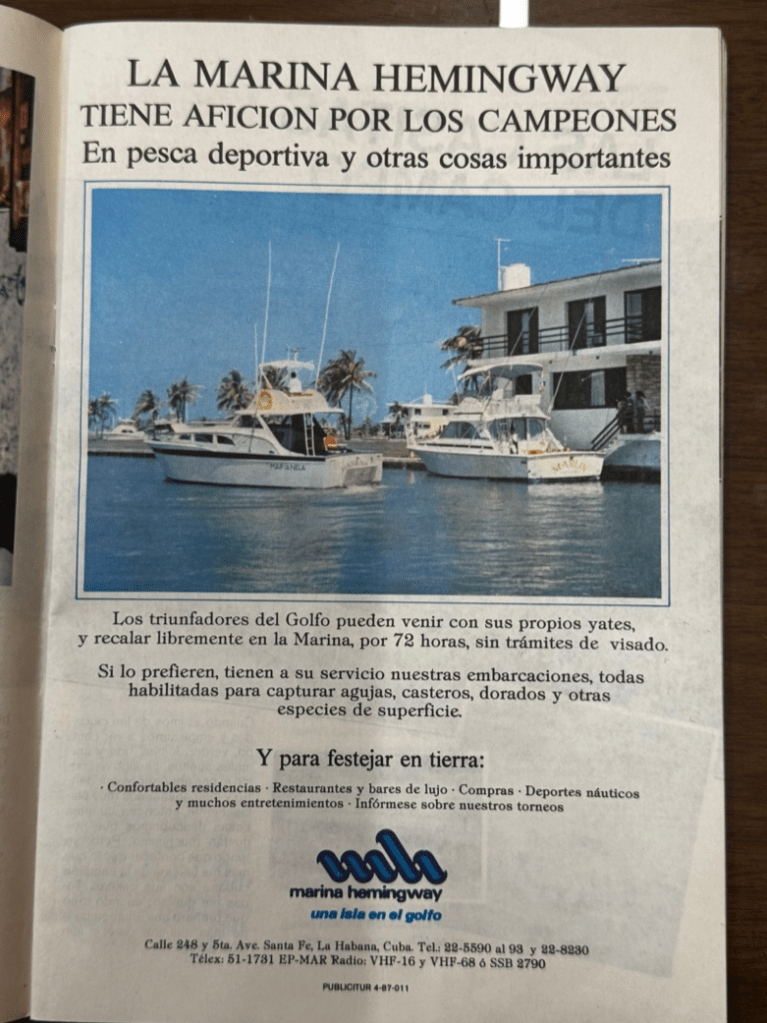

Finally, through my analysis of the Cuban bilingual magazine Sol de Cuba, I found relevant information on the centrality of tourism to the regime’s controversial economic strategy of attracting foreign currency to the island—what can be considered a form of dollar diplomacy—years before the creation of the Ministry of Tourism and the open adoption of tourism as a means to salvage the Cuban economy in the early 1990s. As Sol de Cuba reveals, in the 1980s the regime offered attractive conditions to those willing to visit the island for fishing, including the possibility of renting yachts or entering Cuban waters with private ones free of charge. It also included a 72-hour visa waiver and the ability to stay in one of many luxury accommodations and visit upscale restaurants that offered to foreigners what many Cubans who fought for and supported the Revolution could never afford.